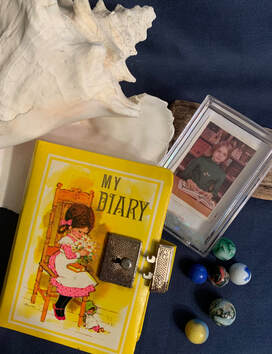

Shane waited until we were out in the driveway before he brought up the memoir. He lifted a hay bale from the bed of his little white pickup truck. He brought the hay for Mom’s ducks and set it down as he spoke. “Your book, Julie,” he turned and faced me. “I cried for days, sometimes I couldn’t get out of bed.” I stood silent; eyes fixed on him as he spoke. This was the first time we had seen each other since he read the memoir. He rested a palm on the side of his truck and continued. “Jan was worried about me. I’d read a little and have to put it down because I’d be sobbing. But I needed to do that. I felt better. Your book helped me so much.” The contract of silence was now just gravel at the top of the driveway. The place where Louise backed the rambler out of the yard in 1973, waving and smiling. Right near the patch of grass where the angel plant sprouted just a few years ago. The statue of Mother Mary stood on the small outcrop of ledge watching us. I took a breath. “Thank you for that.” His big crystal-blue eyes, glossy with tears, looked right into mine with seriousness “Thank you for writing it. There were times I didn’t think I’d be able to finish reading it.” He paused to wipe his cheeks. I nodded. “There were times I didn’t think I’d be able to finish writing it.” I knew how significant those tears were. He has Bardy genes too. We shared a big, warm two-arm hug. Brotherly love. He wiped his face with his shirtsleeve. “I have something at the farm you might want. It’s been out in the garage. I told Ma about it several times, but she never came to get it.” He paused. I waited. “It’s little Mary’s diary.” “Oh my god. You have her diary?” There were few words for me in that moment. It was as if someone offered me the world. Time stopped and for a nanosecond, Mary and I were once again sitting in her little room with the daisy wallpaper. She sat at the small desk writing in her little square diary with the gold lock. I watched intently, memorizing the way she held her pencil and formed her letters. I wanted to be just like her. “There’s not much written in it.” I nodded. “But I think she mentions you.” I couldn’t wait to see her diary. To hold the little book that she wrote in. Run my fingers over the ink or pencil that she put on the page. “Would you mind if I stop by later and pick it up?” “Sounds good. I’ll be home.” He got in his truck and drove toward the farm. Grama and Dziadzia’s house, where Mom grew up, and Mary and I cooked and cleaned, weeded the garden, tended the animals, and played marbles in the driveway. In typical procrastination mode when facing something important, I ran some errands and stopped at the town garage to fill two, 5-gallon buckets with sand and salt. I dropped the buckets at the compound and headed to the farm. The dog barked inside the house, and I could hear Shane talking to his wife. “Julie’s here. Can you get the dog? Come in,” he called. The three of us sat down at the dining room table, and Shane handed me the diary. “Here it is.” “Oh, wow.” Instantly, I recognized the yellow cover, the gold clasp, and the Holly-Hobby-looking girl on the front, with her pink hair tie, matching dress, and white apron. She sat in a chair, chin and eyes lowered, smelling a bouquet of daisies. The small pleasures of living in the moment. Like the moments Mary and I had spent with the seashell pressed to our ear, listening to sounds of the shore. Up until this moment, that shell was the only one of Mary’s possessions I had. I rested my palm on the diary. A book where she recorded her life moments. Slowly, respectfully, I opened the cover, and fanned the pages carefully. Shane was right. There were not many entries. But each one was precious. Noteworthy details from April 29, 1974, in the life of a 12-year-old girl included having roast pork for dinner, and a field trip with her class to the state library in Hartford. “It was fun. I wish we could go again,” she wrote. As Shane began talking, I closed the diary and listened. He shared deeply personal stories I’d never heard before. His experience searching for our sister, Louise. Dad driving the green Volkswagen beetle, Shane in the passenger seat. Driving, endlessly driving, everywhere and anywhere looking for Louise. From town to town, dirt roads, back roads, cabins, and campsites. Shane, thoroughly exhausted, would fall asleep and wake up staring at the ceiling of the VW bug. And afterward when Louise was found, bearing the whispers, the unimaginable anxiety. The alternating silence and chaos at the house. We talked about how that trauma was fused to his nervous system. Horrible experiences and memories stored in the body. As a child in the 1970’s, there was no outlet to process them. He paused and then spoke again about the memoir. “I’d read a little and start crying. I’d have to put it down. But then I’d get drawn back. I had to read it. There were some things that you didn’t have in the book.” He paused. “But they wouldn’t have made it any better.” Coming from Shane, my brother, that was so satisfying to hear. Because it is his story as much as it is anyone’s in the family. And it was absolutely non-negotiable to get it right. Up to that moment, I didn’t realize how important his affirmation was to me. Now, I’ll never forget it. It was twilight when I walked out of the farmhouse and over the large steppingstones of dark gray, metamorphic rock. Their lines and folds and glittery flakes of mica record a history of unimaginable stresses, and hardships overcome. I ran my fingers over the little gold clasp of the diary in my pocket and smiled. This journey has indeed been one of reclamation which continues to unfold in magical ways.

2 Comments

|

To add a comment or view other comments:

click on 'comments' at end of blog. Archives

November 2023

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed